Like many prominent artists, Sarah’s success can be attributed to a combination of favorable circumstances and personal qualities. Wealth was on her side: Sarah was born to a wealthy family in Lowell, Massachusetts, and later married elite Boston merchant Harry Whitman. However, she also possessed a fervor for self-education, a quality that arose from home tutoring as a child, and which allowed her to float into several different disciplines.

Sarah’s formal arts training was brief and in the private sphere; she did not attend an arts academy, which at the time was A Thing You Did. From 1868–1871, she studied painting and drawing with William Morris Hunt (not that William Morris, though they were contemporaries) and William Rimmer. Both of these artists were newly accepting female students, so Sarah was at the right place at the right time. She later studied in France with Thomas Couture, who himself had taught Hunt.

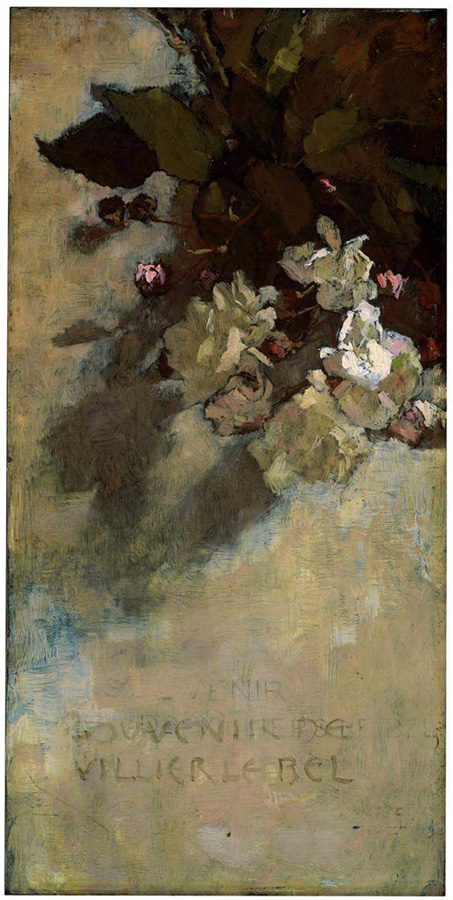

Whitman’s portraits, still-lifes, and landscapes soon landed her quite a few accolades. She was inducted into the Society of American Artists in New York in 1800, which showed her work often. Her first solo show was at the Boston Doll and Richards Gallery in 1882. Sarah showed in several other venues around the city, and received a variety of awards for her painting from near and far.

Though Whitman’s painting subjects were critiqued as traditionally “feminine” subjects, she was also immensely productive in the applied arts, a concept that was considered more “masculine” in her day. Inspired by the English Arts and Crafts Movement and supported by mentors, she began designing book covers, stained glass, and interiors in the 1880s.

If she was renowned for her painting, Sarah gained even more recognition for her stained glass work. She took on various commissions for Massachusetts churches, ran Lily Glass Works, and had several artisans under her employ. Among her most famous glass works were made for Trinity Church in Boston and the Memorial Hall at Harvard University.

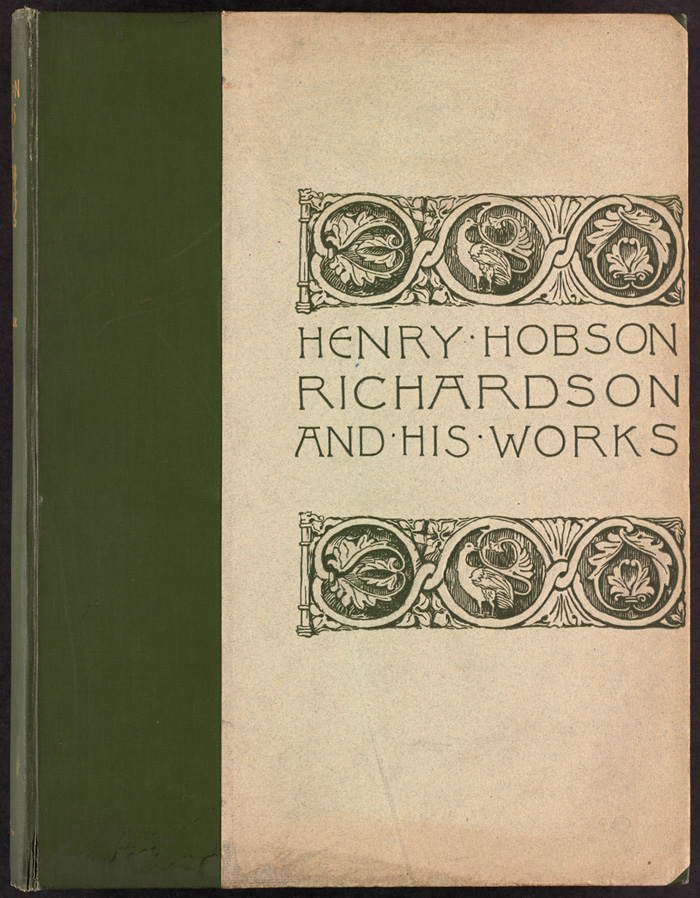

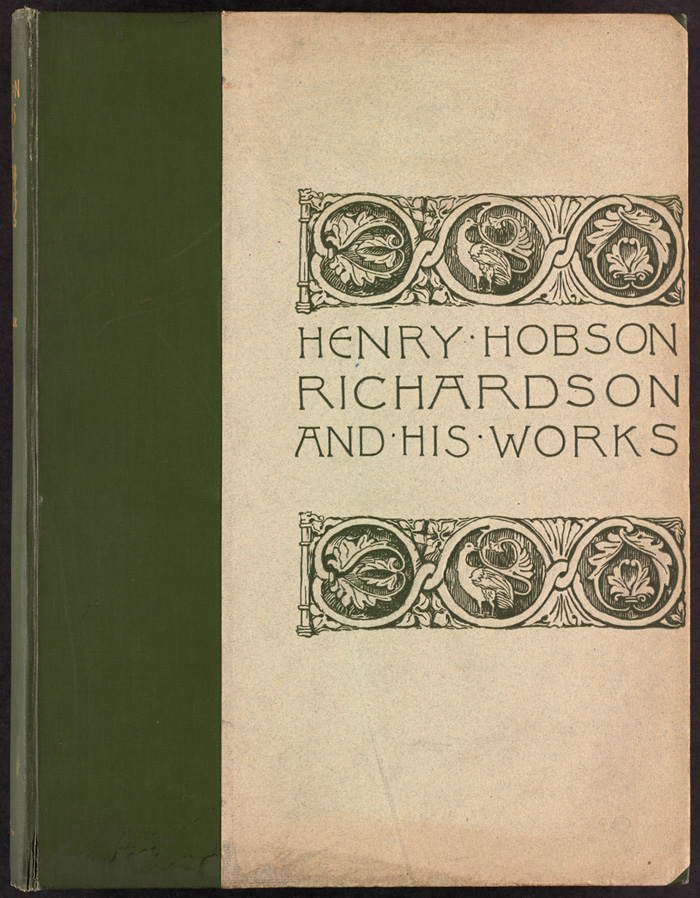

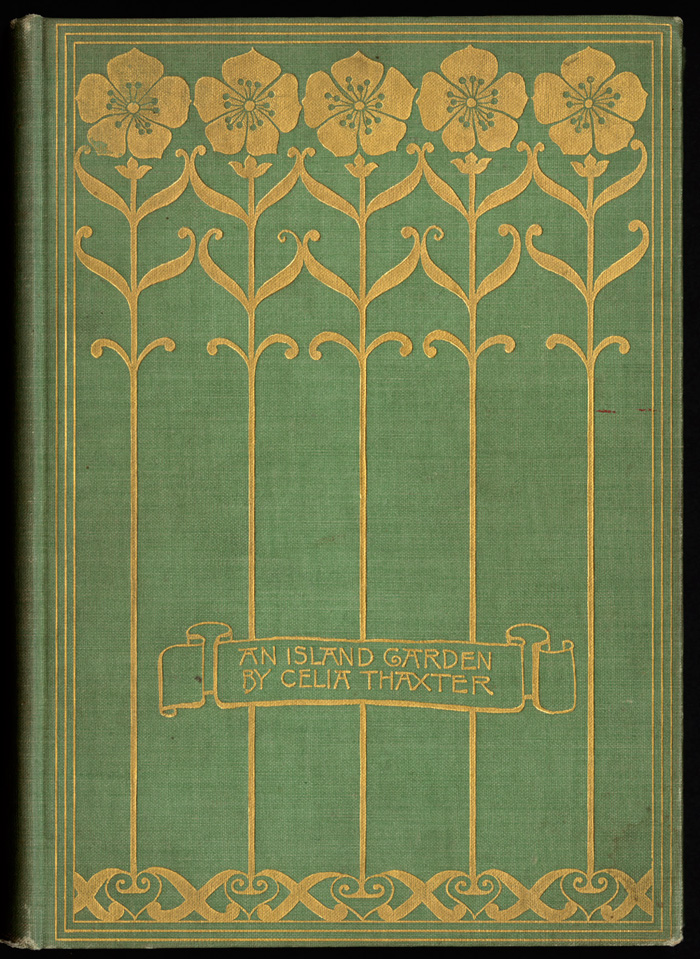

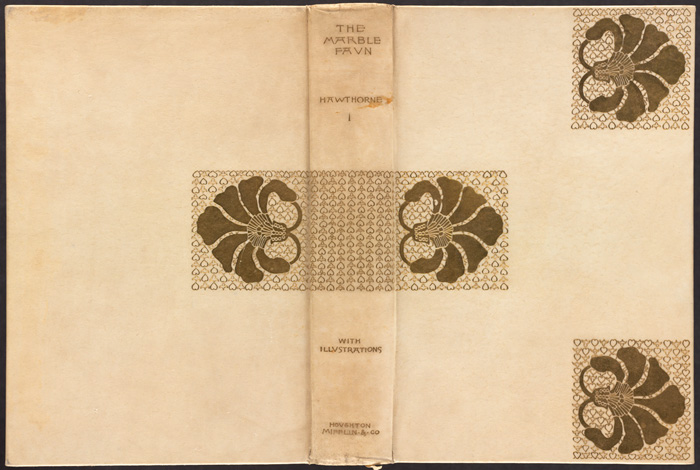

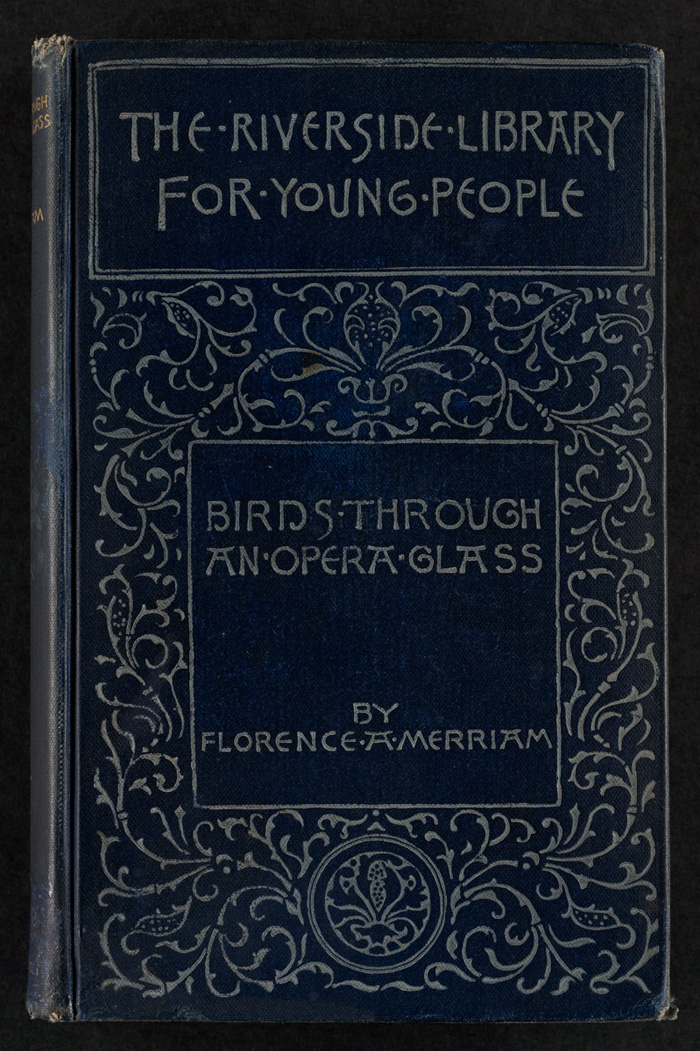

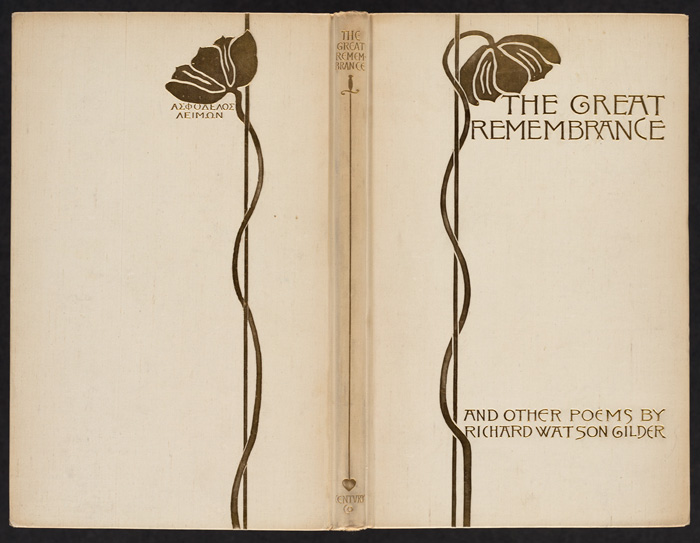

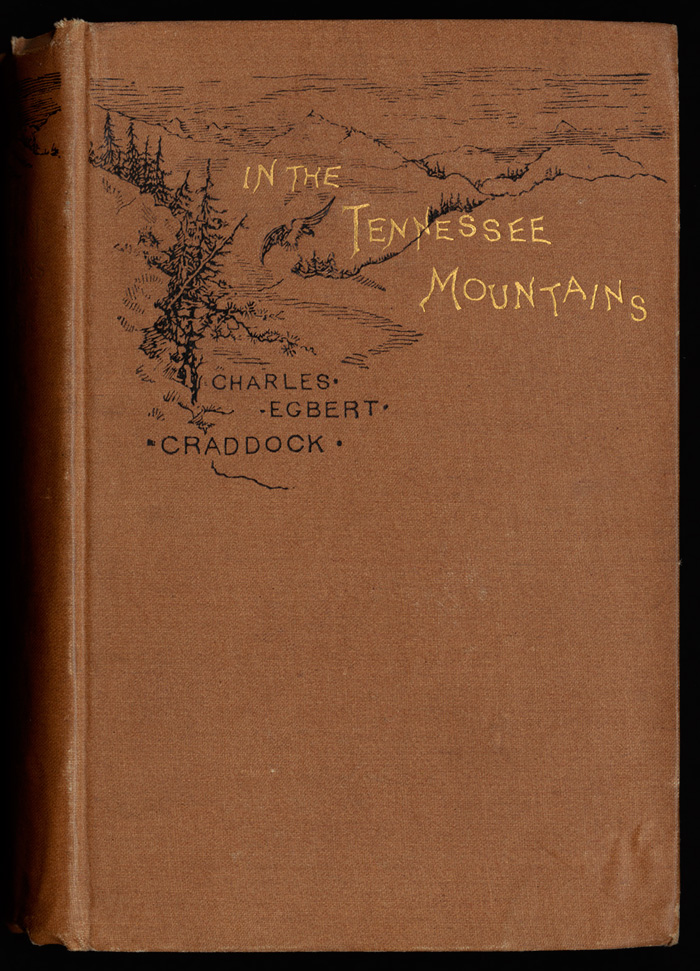

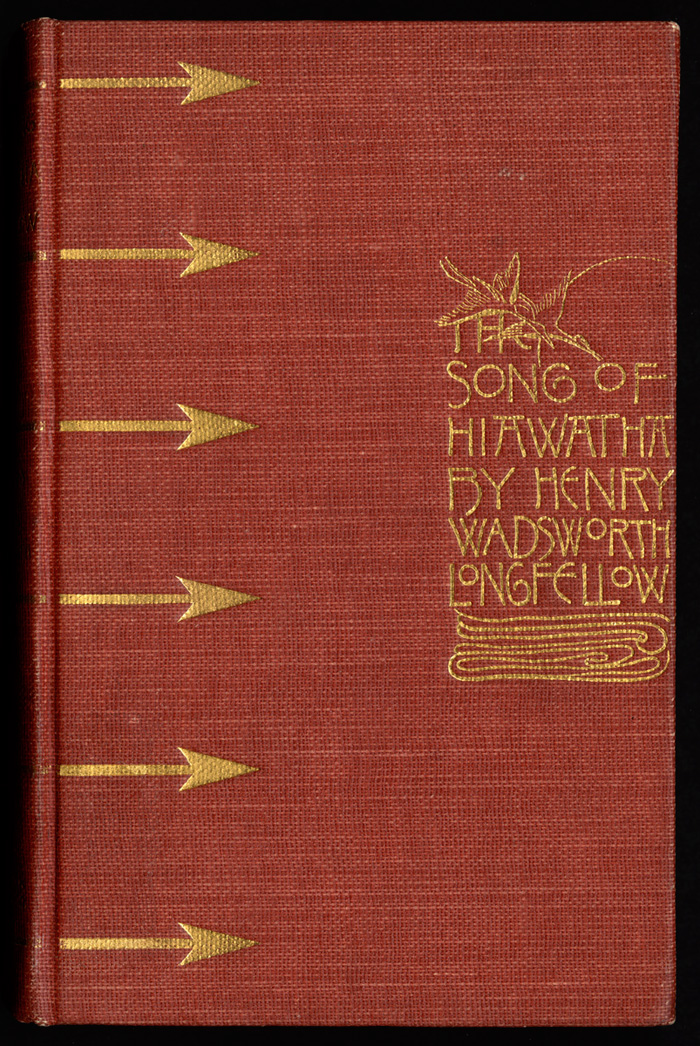

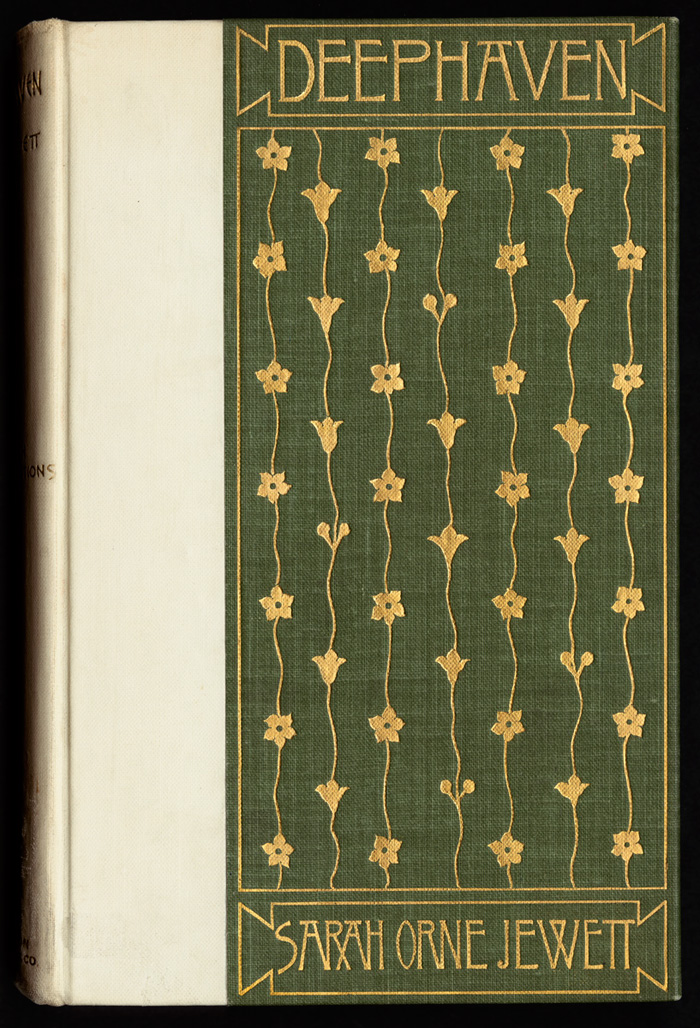

The crown jewel of Whitman’s career are her book bindings, made for Houghton Mifflin. The first woman to be regularly employed to do this work for the Boston-based publisher, Sarah designed over 200 books in a period of 20 years. She worked in the Art Nouveau style, using delicate lines, organic elements, and decorative—rather than illustrative—practices.

Sarah had an affinity for gold foil and simple lettering. Her calling card, used on many of her designs, is a “flaming heart”. There’s a few quite lovely surprises in her oeuvre, like this printed brocade silk cloth.

Besides producing an impressive amount of design work (one of her stained-glass projects included 100 windows!), Sarah was also a poet, teacher, founding member of Boston’s Society of Arts and Crafts Society, and patron of the arts. Though we talk about women who juggle work and home life as if that’s something new, balance was among Whitman’s concerns: how to lead a successful career, maintain a household, and keep up with the very public duties of a philanthropic socialite?

In the end, the massive amount of art and designs that Whitman produced led to physical illness. Though overworked to the point of breaking, she still managed to continue creating in her later years. When she died in 1904, it was as a beloved and influential member of Boston society.

For Further Viewing

Check out the Boston Public Library’s extensive photo set of Sarah Wyman Whitman’s bindings.

Sources